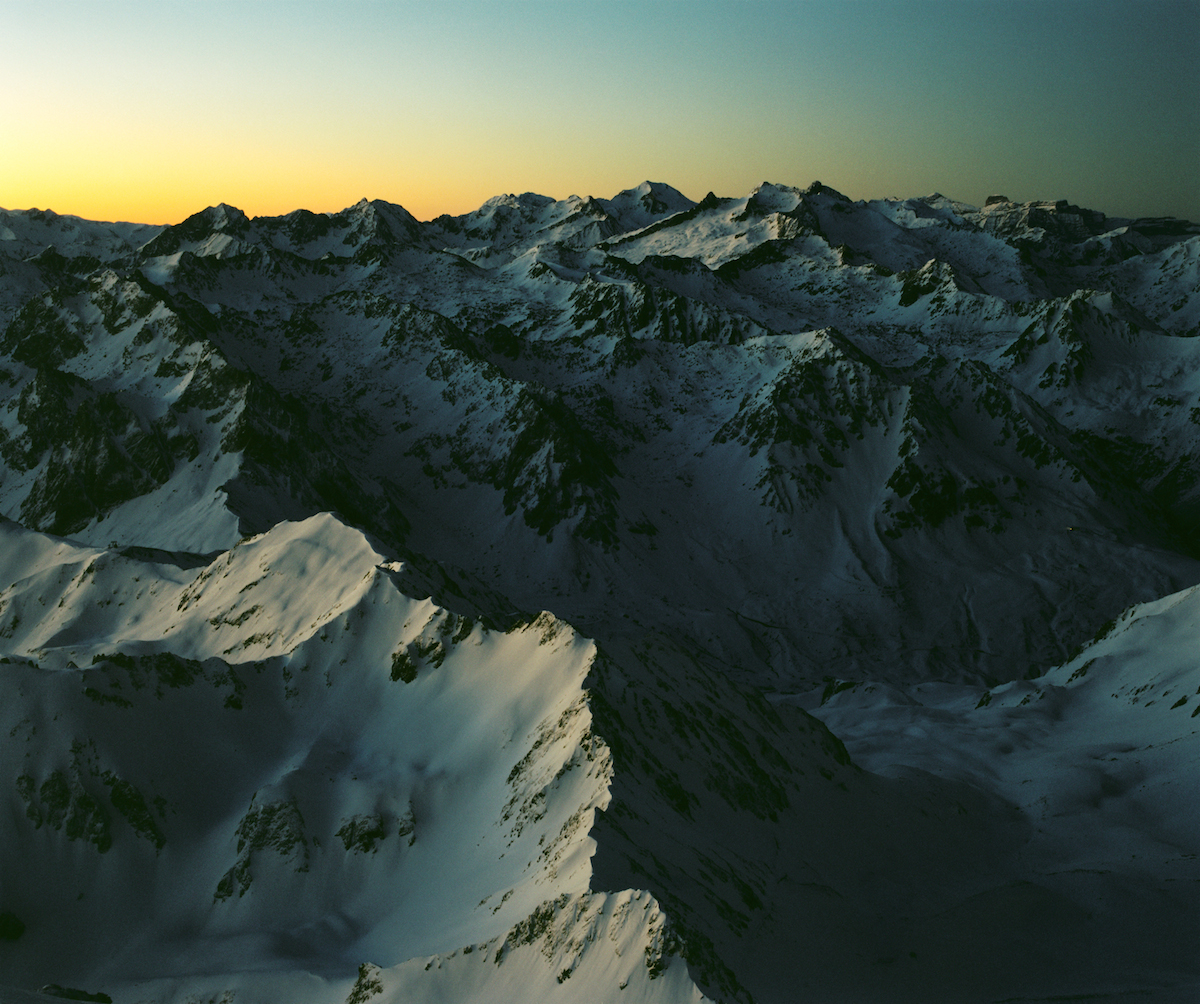

The jet arcs over the plains, carrying the woman toward her family obligation. The closer she gets to her native geography the more raw and receptive she becomes.

Once, years ago, her English teacher said, “If you poke me, do I not squeak?”

It’s like that, the woman thinks, except it’s the world poking, and she’s in public so she can’t make a sound. This is perhaps a side effect of contemporary living: she, a human animal, was never meant to travel so quickly.

Now everything hurts and feels good at the same time.

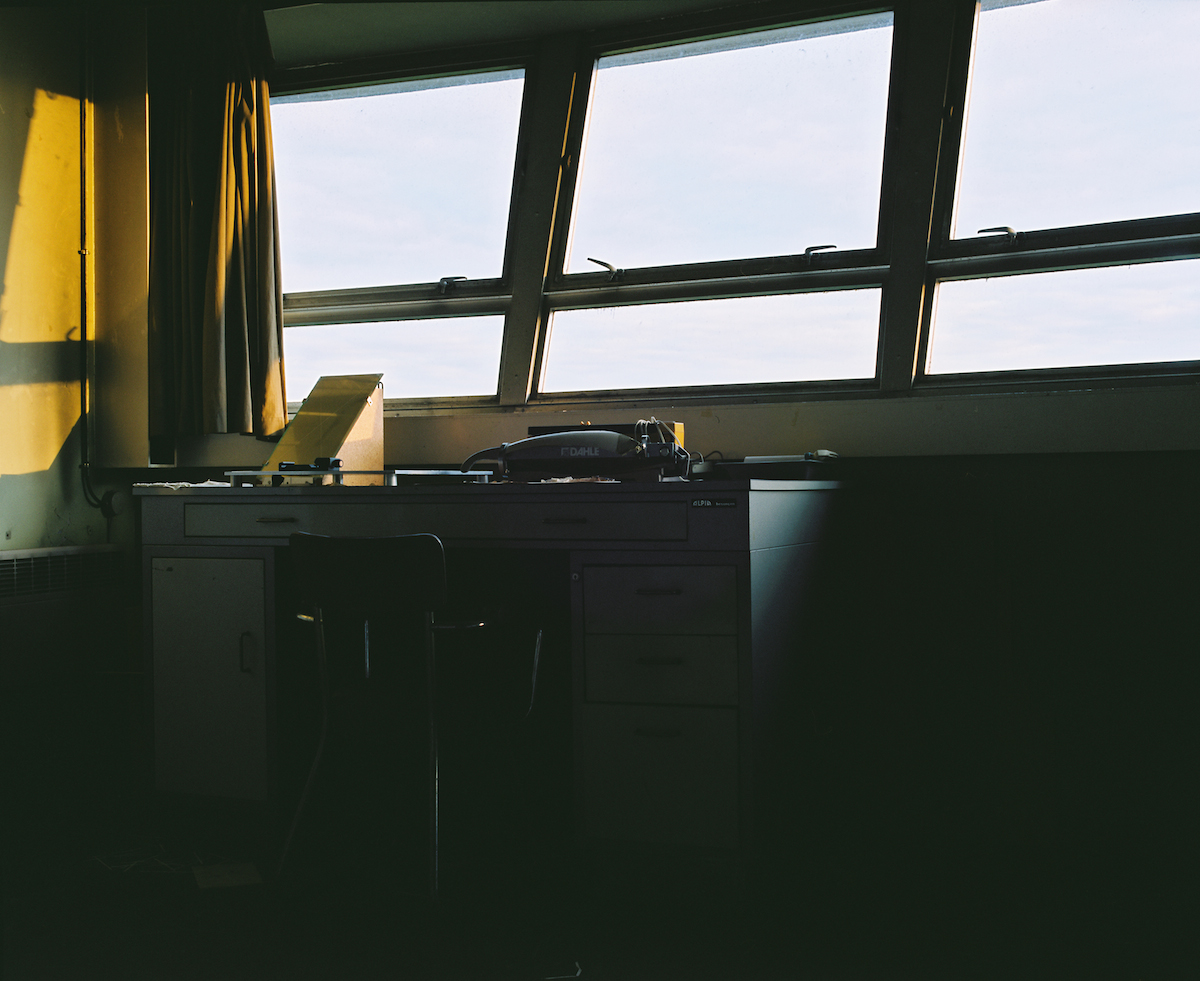

The woman interprets the interior of the plane as a vast, communal living room.

Right before takeoff, a young man in a cropped Capote coat had sauntered toward her down the aisle. His khaki-colored hair swept back toward his crown. The passenger drew herself up taller in her seat, prepared to make conversation because his beauty convinced her he was a good person. But he had swung into row seven and the woman walking behind him—effortless, long-limbed, dark, chic even in sweatpants—folded herself into the same compartment. When she pulled a handful of natural hair out of her collar and pushed it over her shoulder, the woman could smell her perfume.

“Yeah, babe, you’re right as per usual,” said this other passenger. “But the point is that I didn’t know that I didn’t know those things. So how could I have done differently?” And she leaned over to kiss the handsome man with her whole mouth.

Hearing an admission of such a human foible from someone so glamorous, the woman decided she adored them both.

Now, twenty-thousand feet over the surface of the earth, instead of reading her book, she watches them cuddle and share a water bottle. From behind, she can almost believe their cheekbones convey a moral message. It is obvious they have money but it doesn’t matter whether it is earned or inherited; their grace remains the same.

After a while they settle down into a single shape, sharing a long gray scarf like a blanket.

With only thirty minutes from touch-down, they still haven’t moved. The passenger retrieves two mandarins from her carry-on, peels and eats them both, feeling furiously, swallowing the seeds.

Back home, she lives with her own lover in a small house on a cul-de-sac. She thinks of his small teeth and predictable sense of humor. Of his reliability and scrotum. Her phone contains a message in which he bids her a safe flight, as though his courtesy could prevent a plane crash.

Still staring at the couple in row seven, the passenger considers that such a finale might be the best way to go. The least-lonely option. A surge of filial adoration warms the inside of her body. She thinks about the community the three of them might make among themselves, if only they knew she was there, behind them, brimming with love. She imagines touching their bodies as the plane tumbles out of its trajectory, the imminence of death obliterating the personal boundaries that have always disappointed her.

She’d tell them: “I very much believe in God, but only when things are going bad for me,” and afterward her heart would be light. Her new companions would nod silently, thrust beyond language by the extremity of their situation, grateful for her honesty. The woman might smooth the hair away from her temples, or push a tear away from the bridge of her nose. She thinks of their arms around her amidst all the noise, the rushing air, the alarms, the nausea, the crying, the ugliness in everyone’s face.

Her row-mate, a fat person whose elbow has colonized the armrest for an hour, does not factor into this fantasy because it is erotic.

The peels have become sticky in the passenger’s fist but she can’t drop them onto the floor and won’t allow herself to hide them in the chair pocket at her knees. The barf-bag is long gone; she needs a trashcan.

She decides to take her refuse to the bathroom in order to walk past the couple, up and down the aisle, to force them, gently, to contend with her presence as she has contended with theirs. A tiny reckoning. To know for certain if she could ever belong to their little family, if only for the duration of the crash.

Standing, though, she can see their eyes are closed. She sits back down.

Looking out the porthole window, the passenger believes she can comprehend the vastness of the North American continent. Frontage roads parcel the winter farmland into squares, where thicker lines indicate an occasional highway, all of it bound by a single unknown county.

When she looks up again, the couple in row seven has shifted positions and she can see their hands again. The man’s wedding ring—big, custom-made—glitters in the overhead light. The passenger takes a photograph of it on her phone.

The voice, when it comes to her, resonates with the round tones of her own heritage.

“Cute, aren’t they?” he says.

“I’m sorry?”

“It’s nice, right? Seeing a happy couple. It’s a rare thing, anymore.”

“What?”

“Would you like something to drink? Coffee, tea, pop?” This final word strikes her. She wants to laugh until her jaw falls off. Pop. Pop!

“I have these.” Her voice cracks and she shows the flight attendant her sticky handful.

“I’m sorry, hon, I’m only doing beverage service right now,” he says. Wrinkles frame his mouth and deepen when he smiles. The skin along his jaw looks loose, like her mother’s. Is he laughing at her? She wants to touch his hand, explain herself and the photo, but says instead “Well I’ll probably be here when you come back.”