An awful lacuna: Saint Drogo’s letter of resignation

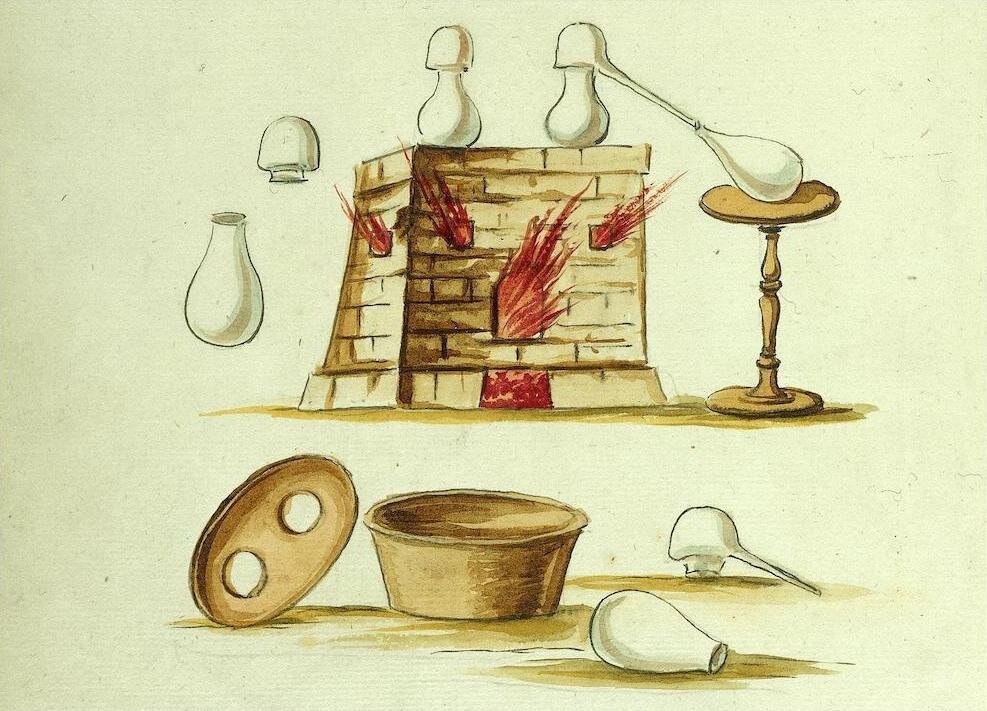

Illustration from Thesaurus thesaurorum, ca. 1775, France

I would like to first make it clear that I had no intention for my tenure as editor-in-chief to be as short as it was. When the townspeople—all corporate shareholders to some degree of Spurl Editions—approached me and asked me to take on this responsibility, I was delighted. As is by now well-known, to protect the townspeople from viewing my hideous appearance, I had moved into a small cell and have been subsisting there on the most rancid barley and the cloudiest water that is provided to me through an opening in the stone wall by a goblin of a man who I am sure only means me harm. Confined to this cold hole, my sole occupation for a decade was studying religious texts, and these texts, by the way, had been seeming more and more hollow to me. By taking on the editorial direction of the town’s publishing house, my day-to-day life would become rich, or so I believed. I was provided pen, paper, and the many manuscripts that had been delivered to the town but had gone unread by a previous editor whom I shall not name. Among these manuscripts I made a sublime discovery: The Cheap-Eaters, a novel by Thomas Bernhard, describing a man who regularly eats lunch and walks through parks. I did not hesitate: I made the acquisition and worked diligently on its production. The handsome volume was soon shipped to towns, villages, and hamlets throughout the southern foggy region.

Yet it was not long after this that the majority shareholder of Spurl Editions, who happens to be a trustee and reports directly to corporate counsel, came to my cell for a meeting. The shareholder held a slim volume that a press in the next town had recently published. I immediately recognized its name and design, but I could not fathom why this book would be a subject for our meeting. The shareholder slipped the book to me through the opening in my cell and asked me to turn to the copyright page. He asked if the page disturbed me, to which I candidly answered no. Then I saw it. Five words, or four, if two words that are hyphenated are to be counted as one word.

Printed on acid-free paper.

“As an editor, your responsibility is the copyright page, correct?”

I nodded, although this gesture was absurd, given that the shareholder could not see me through the stone, and I was not so short that I would be visible through the opening.

“I never thought to add this language. I have to deeply apologize. What does it even mean?”

The shareholder snapped back, “That’s neither here nor there.”

I remained silent for some time, hoping that my apology would resonate with this important person who held so much of my life in his hands. I did not want to return to a life of studying religious texts. It was clear that I had made a grave error, and that the shareholders would soon be meeting to discuss my fate; corporate counsel was likely aware of the error, too.

“We will need to consider this further,” he said. “The workers have been instructed to cease production until this is corrected. Goodbye.”

I looked at the copyright page again. Printed on acid-free paper. My head swam; I wanted to vomit. My thoughts began to spin out. Would this painful absence hurt readership? This awful lacuna. Surely there was something superior about acid-free paper compared to acidic paper. What kind of person would go from stall to stall, picking up and comparing books, and ultimately choose the book printed on acidic paper and not the one printed on acid-free paper? Only a madman, only a person who wanted to flout convention and stain his fingers with acid. As an editor I did not want this kind of reader. The shareholders of Spurl Editions did not either. When I took on this role, I envisioned clean, healthy readers, their hands spick-and-span, their minds ready for wholesome reflection. Not filthy greedy fingers whose skin was peeling off.

The book, The Cheap-Eaters, entered my mind again. Obviously I had failed it. The man who ate economical lunches and walked through various parks would be misunderstood now. I knew this. It had reached the wrong readers. They would ascribe a nasty quality to it: call a logically ordered book “obsessive.” Sympathize with insignificant minor characters. This was bad enough, but on top of this misery was the fact that my failure would allow the other towns’ presses to flourish. This was a year when my town needed every bit of help. Our doctor had been fatally mauled by a beast from the mountains, and the townspeople were falling ill with strange diseases, so that they could not work in the same diligent spirit as in years past. In trying to make our situation better, I had made it worse.

Well, there was no choice then. I did not want to wait in agony for the shareholders to meet, for corporate counsel to explain to them what I had done wrong. For them to vote.

I would rather step aside. It has been a humbling and gratifying experience to be editor-in-chief of Spurl Editions from April 1183 to August 1184. If there is one positive thing that I can express about these recent events, it is that they have brought me closer to God. No longer do I dread my existence. I am a “cheap-eater” too. I embrace eating what the goblin serves me through the wall, whatever it is. It is a sign of the goblin’s love for me. I embrace my religious study, for it keeps my fingers clean. My failure will not define me.

I will end by expressing my sincere apologies to all who were affected.

Saint Drogo