Illustrated Guide to Amsterdam and Environs

Chapter Nine

Walks through Amsterdam

Guided by Monsieur de Bougrelon.

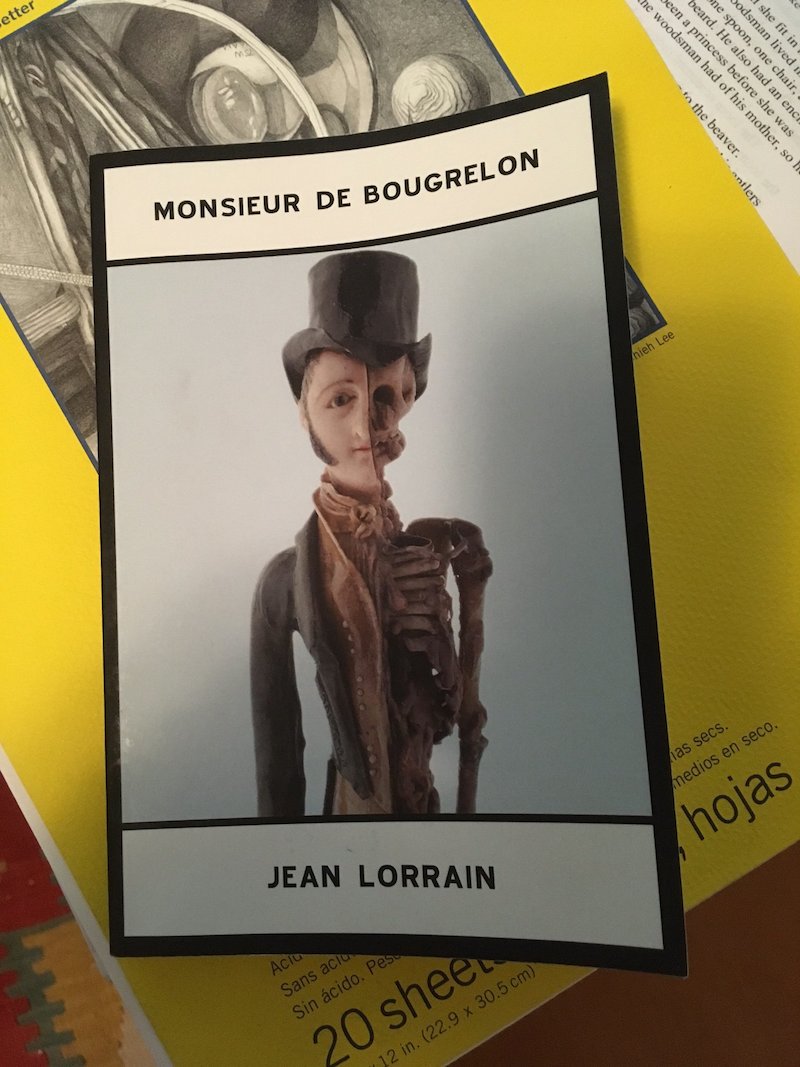

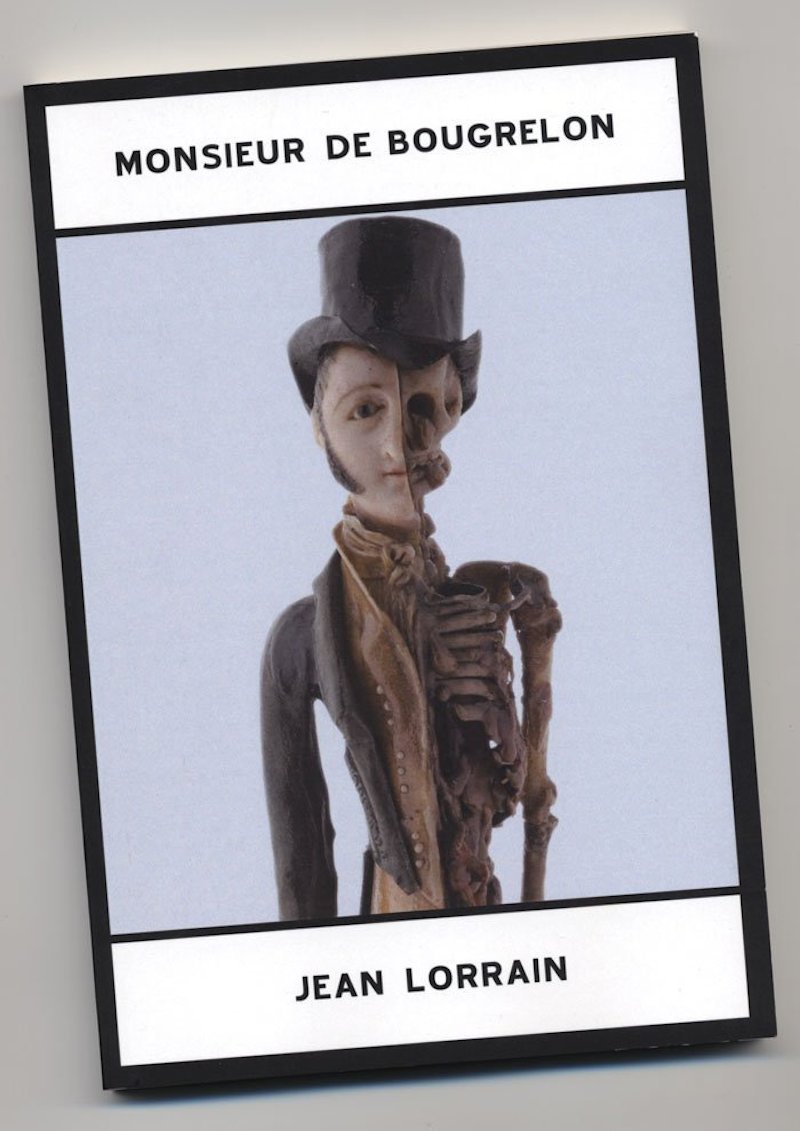

Do you happen to know the hero of the amusing little book that Jean Lorrain wrote about Amsterdam and which bears its hero’s name as the title, Monsieur de Bougrelon?

As I look at you, rows of national tourists seeking joy as well as comfort, who each year set out to see the world’s eighth wonder, which is to be found in the world’s ninth – our great capital, right? – and if I would browse through your city bags, purses, suitcases, florid valises, travel baskets, German baskets, coffrets, sacks, pompadours, satchels, and bahuts with the curiosity of a landlady looking through the belongings of a new tenant who is already a month behind on the rent, then I would probably find a copy of Warendorf’s Travel Library, which you have been reading as compensation for the monotony of the journey, or an illustrated magazine like Die Woche, but I won’t even find mention of Monsieur de Bougrelon’s name in the newspaper that is wrapped around your “sandwich for the road,” a sandwich that is a symbol of the tenderness of a mother, sister, wife or girl, but which is nevertheless doomed to never reach its destination.

The “sandwich for the road” has become like the Chinese man’s prayer, which keeps existing but has no more meaning. Like the tragic remains of ancient times, of carriages and track boats, it has survived, a gray old man with a wrinkled face, a stranger amid modern comfort and modern luxury. The “E pluribus unum” of each station has become an epitaph for that “sandwich for the road,” as Amsterdam offers so many opportunities for one to refresh oneself well and at little expense that you are right to offer it to the boy who sells you The Nieuwe Rotterdamsche, Weekblad, Telegraaf, and Handelsblad, thus stopping his vocal trumpet. You are right to rush to a restaurant as soon as you arrive. Well, no, you are not right: why would you want to do that without our great friend, Monsieur de Bougrelon?

Look at him standing there in his long fitted frock coat, a large top hat bought at Meeuwsen’s Hat Shop rather crooked on his head, a truncheon-like walking stick in his hand, a pretty scarf tied around the most gracious of collars, a pair of Dent’s gloves from Mr. Sinemus’s store on Leidsestraat, and with a face you swear you have seen someplace before.

He already took hold of us, already joined us, already introduced himself, already pointed out the way around the tunnels of the Central Station to us, which is built too high, as compared to the museum, which is built too low.

Monsieur de Bougrelon, placing his walking stick with force into the ground that comes from the seas, leads the way to the Hotel Van Gelder on Damrak. This is quite a suitable place for you to stay, as your fellow Dutchmen possess three characteristics that make them excellent for hotels: they are solid, simple, and tidy. Look here, does not everything shine brightly? Look at this glassware, washed the way it should be, with a cold bath afterward, to get the pure lucidity that reminds one of jewelry. Ah, decency is the sister of tidiness! Really, you could swipe a finger underneath the cabinet and the bed and then swipe it on the white sheets without sullying them.

Rising already, Bougrelon glances at a large collection of bottles of “Kaiserbrunnen,” the most excellent of mineral waters, which had just arrived at the hotel again, and then you are obliged to follow him down Damrak, across Dam Square to Kalverstraat while he unfortunately only verbally burns down the new Stock Exchange and lavishes praise on the Royal Palace, whose silvery chimes ring out above the head of the lonely virgin who, he thinks, has done wisely by turning her back to all the ugliness that is behind her.

“The aorta of the city,” he says, “this Kalverstraat, which is only narrow so that no modern electrical tram shall disfigure it with its rows of gallows, whereupon beauty has been hung by executioners. We do not need a tram in this street. One walks through it like one walks through a beautiful and interesting book, and it is over before you realize it.”

Monsieur de Bougrelon suddenly stops in front of one of the big plate-glass windows of a stately house with a high façade.

“Beauty originates in the south. Here you are standing in front of the art trader Buffa’s gallery, one of the great attractions of your capital. The De Medicis brought the fine arts from Italy into my beloved France. But the Italians traveled farther north and it is the Lurascos, the Cossas, the Grisantis, the Boggias, the Valciollas, and the Buffas who brought art to your ancestors at the beginning of the nineteenth century, which was badly deteriorated by then. The Buffa brothers originally traveled to fun fairs with their etchings. The Venice of the North appealed to them and they settled here, on the Weesper Square, right near the Amstel. The sons expanded their father’s business and soon Buffa and Sons was of eminent importance in Amsterdam.

“In 1836 the firm came into the hands of another son of the land of Dante and Petrarch, Mr. Caramelli, and today Mr. J. Slagmulder and Mr. P. J. Zúrcher are the owners of this booming art gallery, built across three houses on Kalverstraat.

“But you need not stand outside merely looking at the windows displays, although there is plenty of beauty to find there already. The rooms inside are free for anyone to enter and give an overview of the most beautiful and best Dutch painters, old and young, and more; beside the Israelsen, Marissen, Mesdags, Voermans, Witsens, and Mauves, you will see Daubignys, Montecellis, Daumiers, Henners, Ziems, Decamps, Millets.

“Quite often, when my old heart longs for the art-loving shores of the Seine, in whose wide stream the Louvre is reflected, I wander in front of this sanctuary of the arts and never do I leave unconsoled.”

(pp. 143-146)