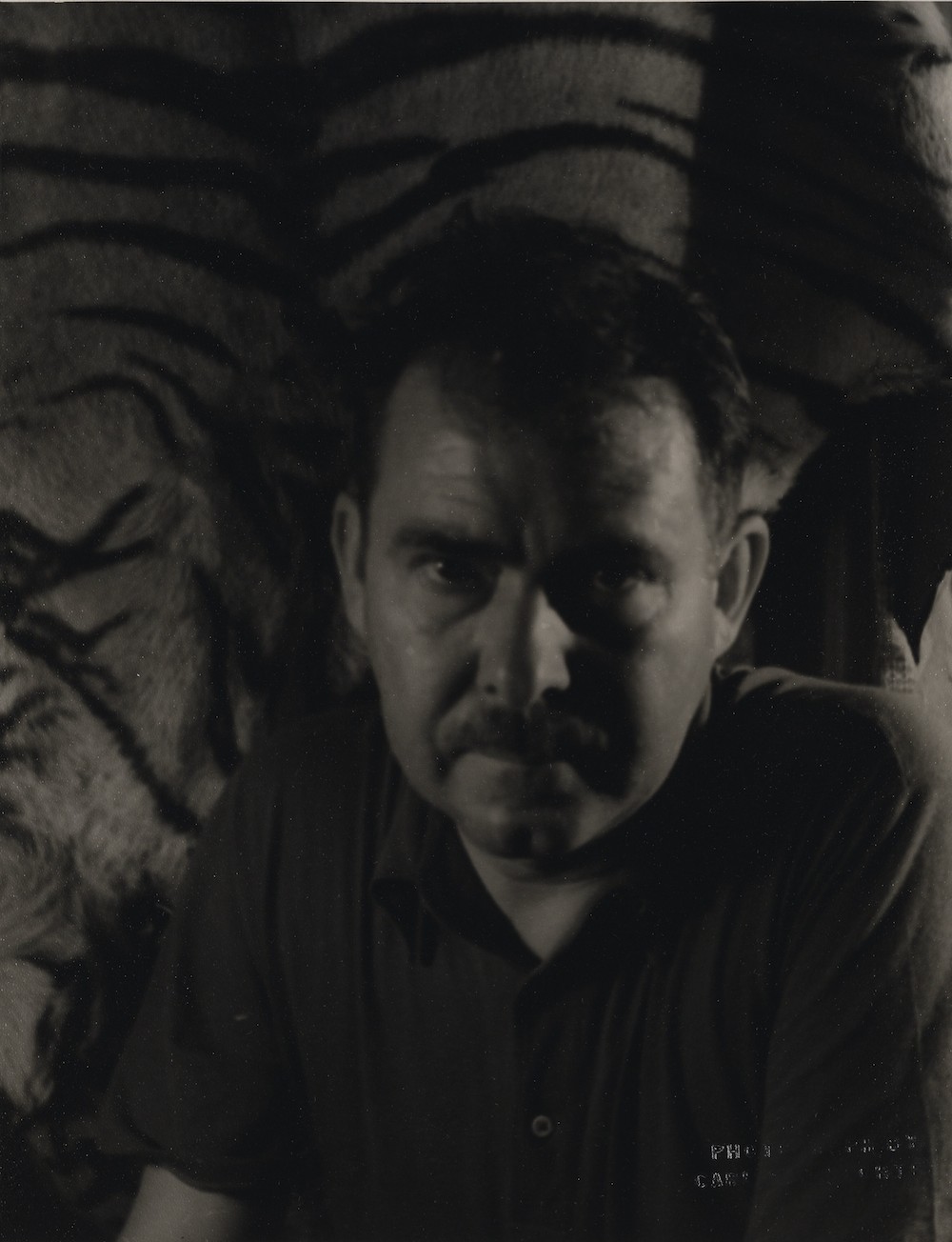

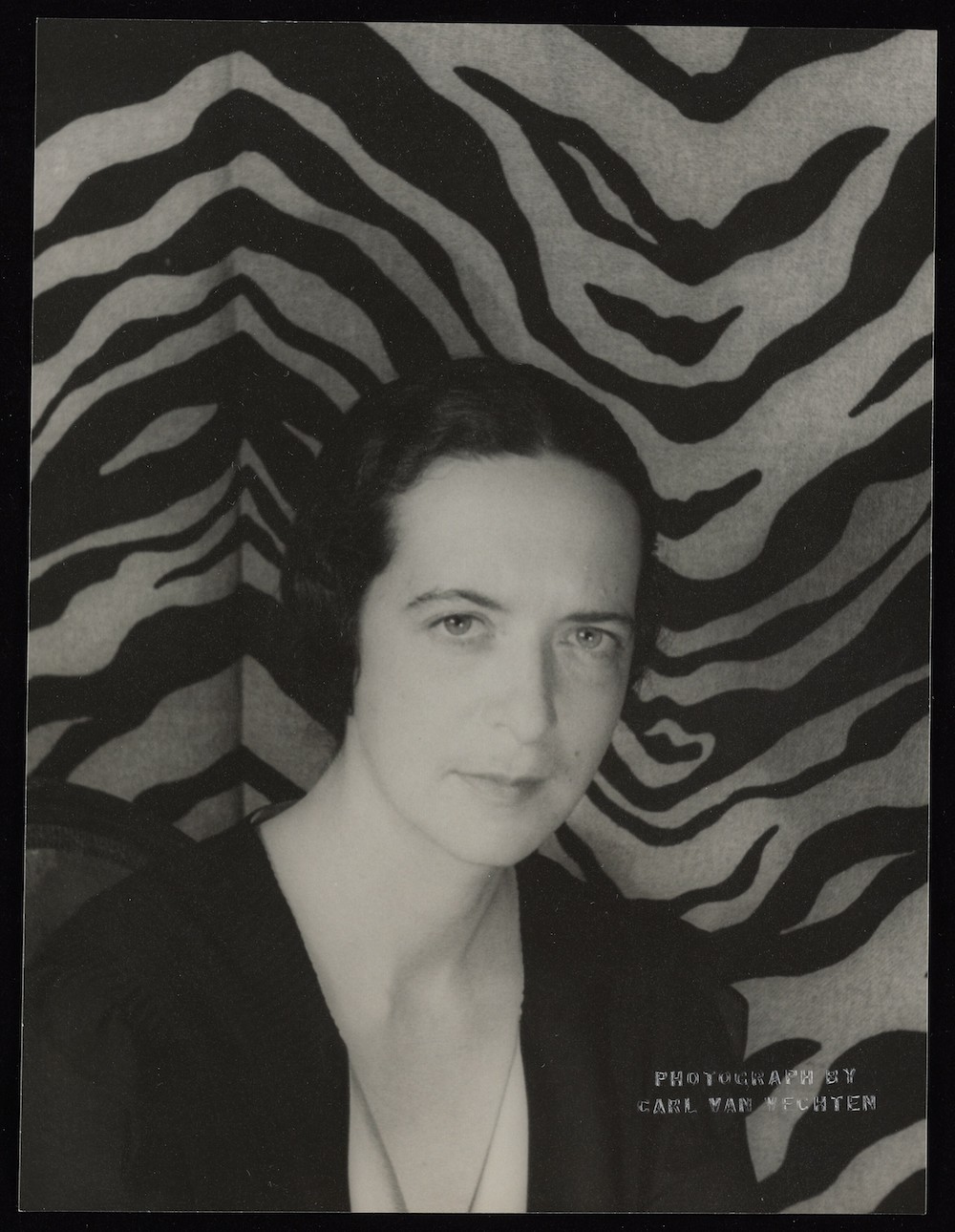

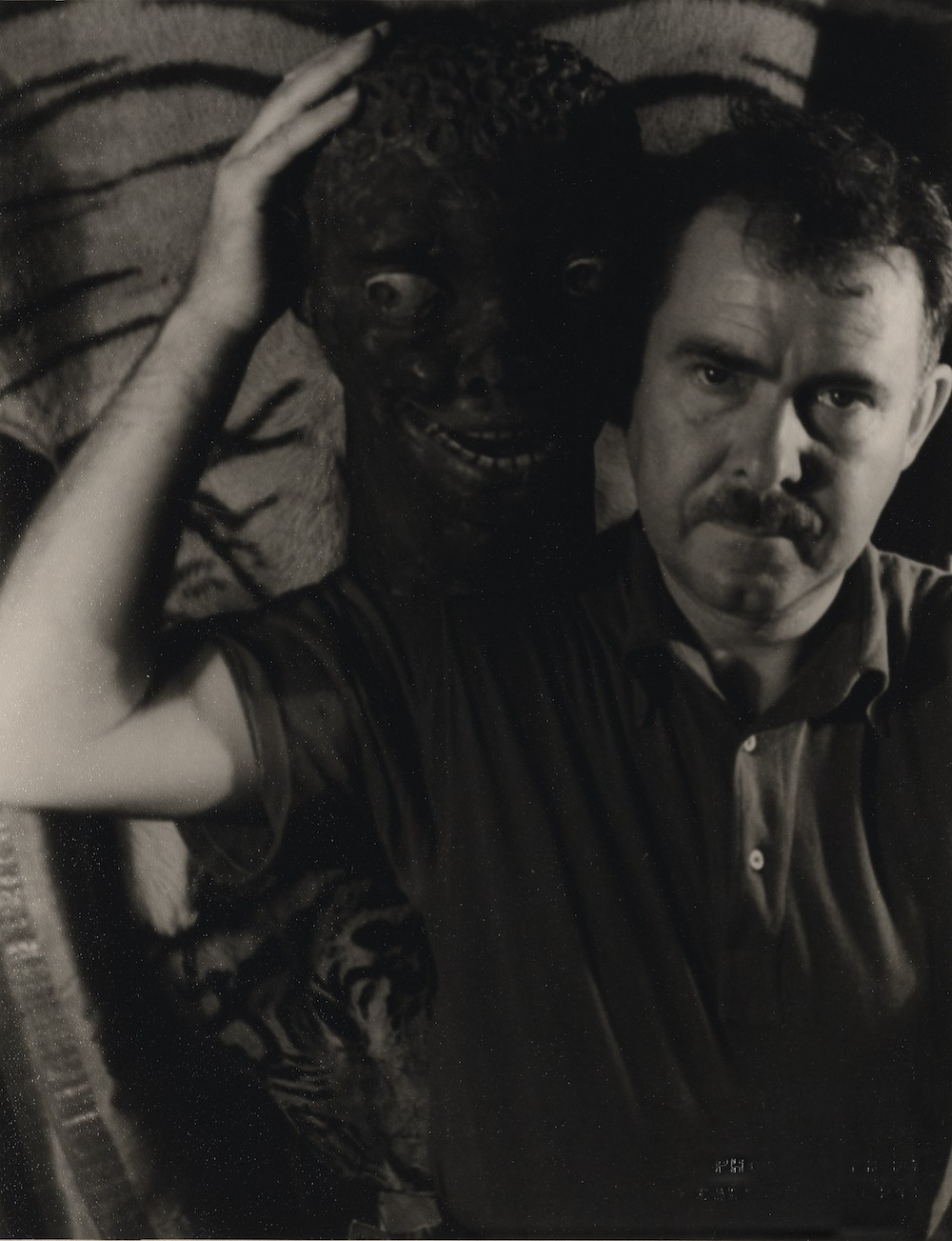

Usually we took them in our stride, offering an apéritif, lunch, or dinner, and sometimes a trip in one of the little boats across the harbor to Les Sablettes. But when Carl Van Vechten and his vivacious wife, Fania, arrived, they expected more than that. At least, Carl did. For all his sophistication there was a streak of naïveté in Carlo that was perhaps part of his charm.

We took him and Fania to Charley’s, where we enjoyed our dinner, and then Carl announced that he wanted to visit a Toulon brothel. I am quite sure he would never have asked to visit one in New York or any other American city, but because he was in France and because Marseilles had a certain reputation and Toulon, actually, was not far from Marseilles, he expected Toulon to be filled with houses of ill fame, all of them very exciting and special.

The truth was, Willie and I were the last people to act as cicerones in the area of commercialized vice. When Willie wanted excitement he had his own ways of creating it, and the synthetic stuff likely to be found in brothels would have bored him to death.

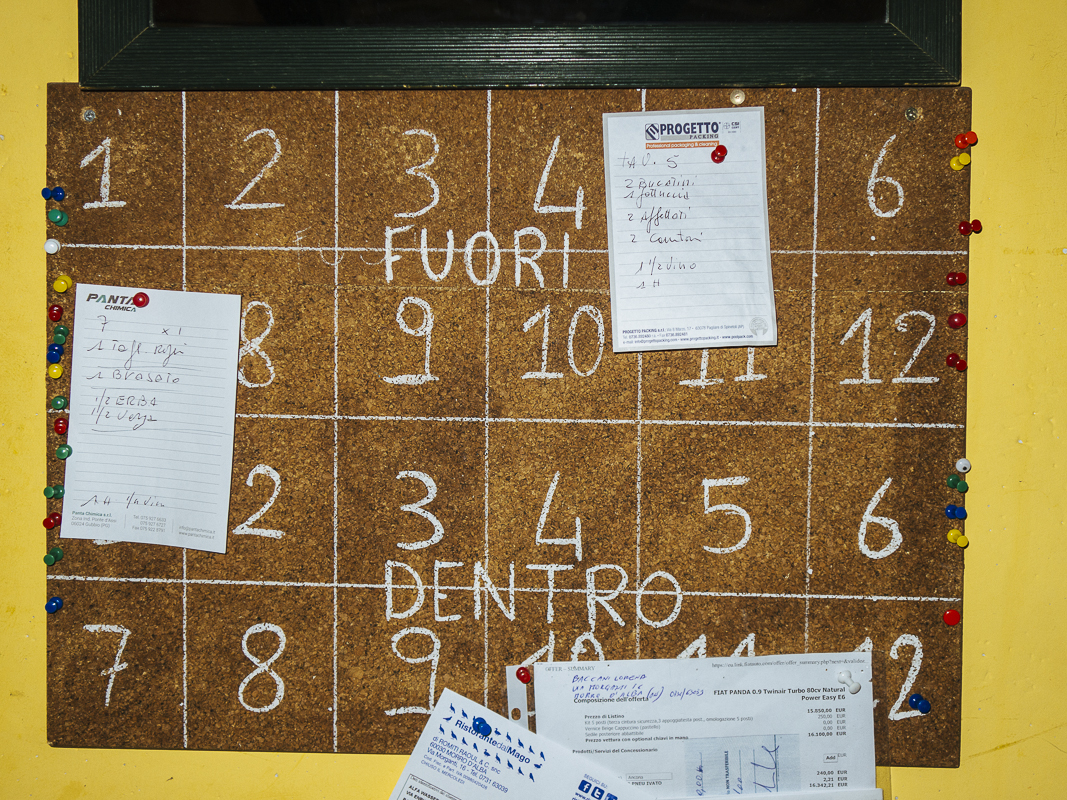

However, since all our friends expected us to show them the sights, we walked with the Van Vechtens to a part of the town that was almost as unfamiliar to us as it was to them. As I remember it, there was a row of houses over near one of the gates in what remained of the wall that had surrounded Toulon in medieval times. Over each house, on the glass transom, was written in elaborate lettering, a name: Adele, Nanette, Mignon, etc. And over the name was a naked light bulb, painted red.

We went along the row and came back to the first one, Adele’s house, because it was the largest and therefore promised the most elaborate entertainment. We rang a bell and the door was opened for us after a while by a rather drab female whom we took to be a servant. She led us into a large square room, and to a wooden table along a wall. She took our order for drinks, and disappeared.

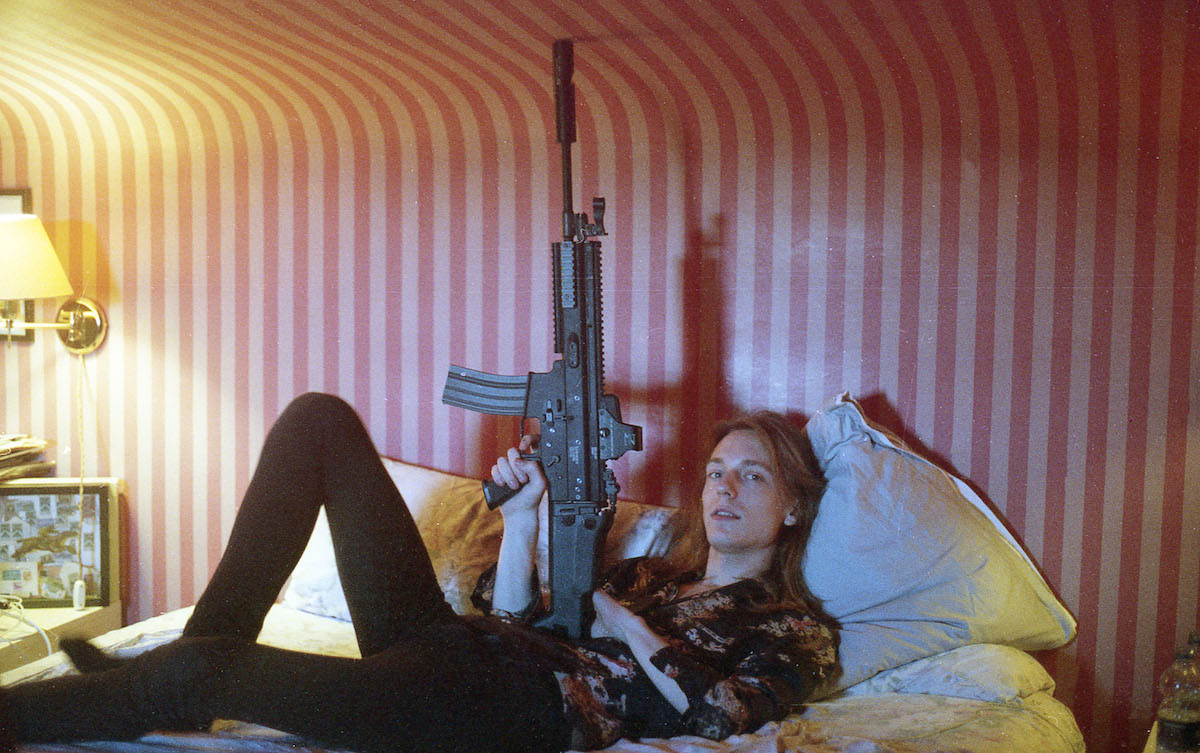

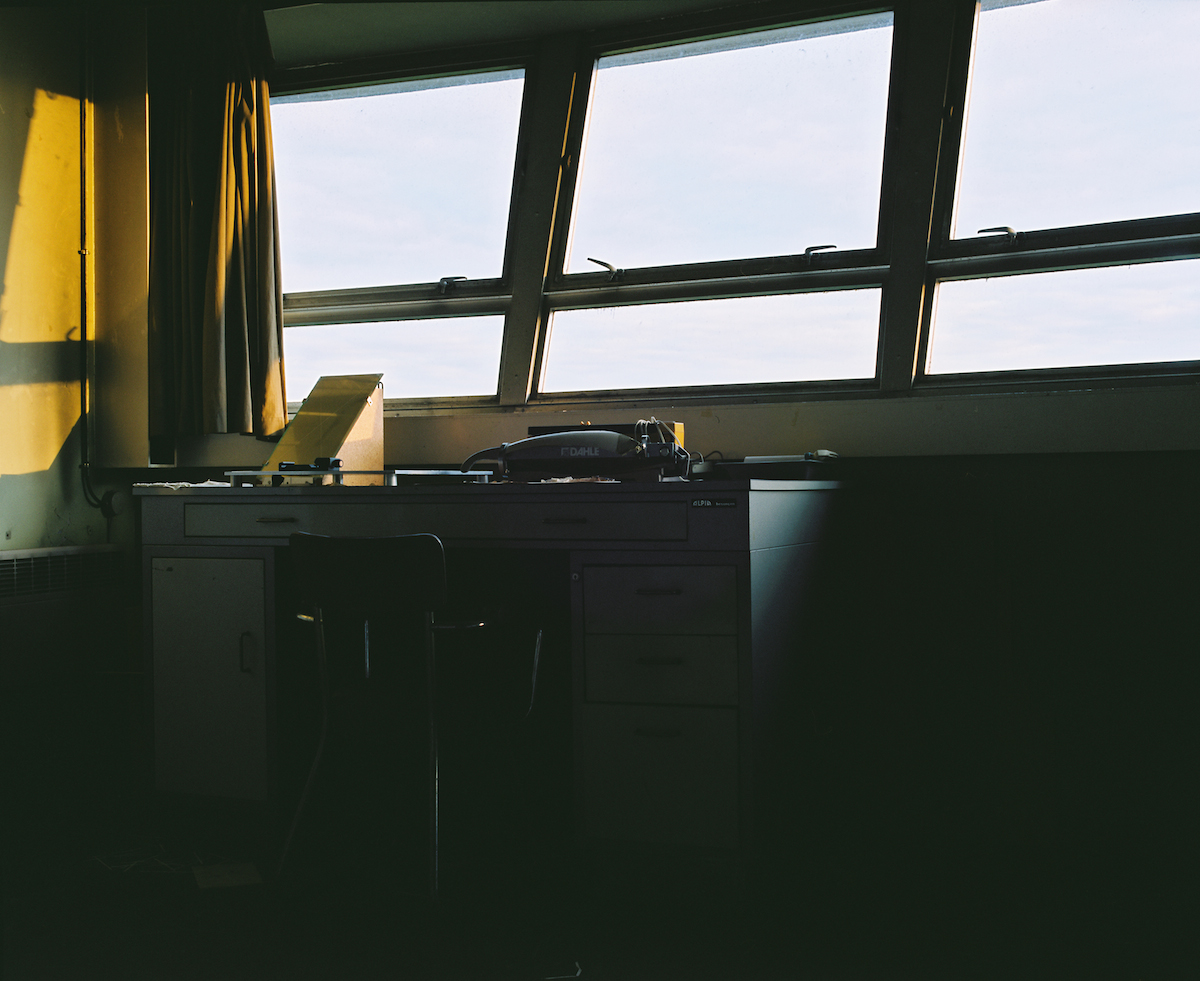

We looked around. Anything less like a house of joy would have been hard to find. The floor and walls were bare. In a corner was an upright piano and a bench but no piano player. In fact, a lugubrious silence filled the room, and we waited for our drinks with the hope they would brighten things up, at least for us. They took a long time coming and when they arrived were served by a short squat little man with a handlebar mustache, wearing sloppy trousers and carpet slippers.

Carlo asked him where everyone was and he shrugged his shoulders. Adele was not working tonight, he said, and her regular customers had the delicacy to stay away. It appeared that Adele’s father had just died, and the house was in mourning.

However, he added, as we started to leave, there was one girl on duty, “une brave jeune fille,” and he would send her to us immediately. In the meantime, since the “girls” were permitted to drink only champagne, would we not like to order a bottle? Of the very best? It was obvious that he disapproved of our marc, the local eau de vie, which Willie had ordered for all of us in a vain effort to show we were not tourists. The French were always great sticklers for form, and in the circumstances champagne was the proper thing to drink, even the sweet, sickening stuff he opened for us with a pop and a flourish. It didn’t make us feel any gayer.

Pretty soon a young woman entered the room and came up to our table. She was wearing a plain dark skirt and blouse and she looked vaguely familiar. It was the little slattern who had opened the door for us, only now her dark hair was brushed and she looked cleaner. She sat down with us and accepted a glass of wine. Then she looked at us expectantly.

Willie spoke to the girl, using the patois of the region, and Carlo listened as if he understood, and I grew very nervous. I looked at Fania and she looked at me and we didn’t need words in any language to understand each other. We made an excuse and asked the girl to show us where the powder room was, just as though we were at “21” or the Colony, and if the girl looked puzzled it was only for a moment. She caught on quickly enough that we wanted to talk to her.

When we got out of sight, Fania took a handful of francs from her bag and I found fifty of my own to add to them. “Say no to the Messieurs,” I managed to say. She understood, parfaitement, and thanked us. After all, with a death in the family . . . you understand . . . and the funeral tomorrow . . . one didn’t feel exactly like . . . It was understood. And she thanked us.

Carlo and Willie were as relieved as we were to be out on the street again. The hour was late, and the Van Vechtens were catching a train for Italy early in the morning. We took them back to the Grand Hotel, still good friends in spite of the fact that we, as well as Toulon, had failed to live up to our reputation.