From CHAPTER THE FOURTH

In which, as Signora Palmira

remains rather frustrated,

another character leaves us.

He left, as is only natural, for his wedding journey. He had told the bride that, for their honeymoon, they would be going to the city of the Saint, and she had asked him if by chance he was referring to Padua, the city of Saint Anthony, which she had never seen but which she didn’t have much desire to see, and he had replied that it wasn’t Padua, and so she, a bit audaciously, had thought of San Remo, where at that very time they would be holding the Song Festival that ever since she was a little girl she had watched on TV, all three nights, before some obscure oversight committee had imposed on an entire country to do without two of the three. There, she thought, her strange and in many ways gloomy husband, by taking her to San Remo for the Festival, was fighting the arrogant callousness of people who, their own hearts having hardened, wanted everyone else’s to harden too. Fascists, Palmira called them, even though now, by matrimony and wealth, she was no longer a proletarian.

But, instead of San Remo, the city of the popular songs, Signora Palmira came to find herself in the city of Saint Francis of the downtrodden, Assisi, where, shit, there was a festival of sacred music going on.

However, it wasn’t for the sacred music that Augustus the Second had made the long journey to a place that was, all in all, out of the way, nor for the olive trees that “made the slopes pallid and smiling with sanctity,” nor for the clear sky and breathable air. He had pushed himself all the way there for the sole purpose of admiring, in person and up close, the famous painting by Giotto whose photographic reproduction he had hung in the Administration, on the wall opposite his desk.

Indeed, upon their arrival in the town so sweetly perched on its hills, Augustus the Second, even before going to drop their bags at the “Sister Moon” pension, where he had reserved a double room with bath, ran, holding his recent bride by the hand, to steal his way into the Upper Basilica, where he effortlessly discovered his painting. Nobody had ever told him so, but he knew that it was right there where indeed it was.

He stood before it, immediately fascinated, but then also a bit amazed and bewildered, not so much because of the extraordinary nature of the deed represented, for to him there was nothing extraordinary about it, but rather because, voila!, through the art of a consummate painter, something so fundamentally normal as chatting with a few songbirds was portrayed as sacred, or even miraculous, and in the end he felt, not without trepidation, caught up in the sacredness. And as this sort of spiritual uplift pervaded him, he kept on holding his recent bride by the hand, maybe out of distraction, or maybe because unconsciously he was hoping that even she, perhaps helped in some way by the flux of emotion that he himself was undoubtedly emanating, would rise to the sphere of superior perception and supernatural relation that we are accustomed to calling mysticism. But Signora Palmira, on account of her nature and constitution, was not cut out for such celestial journeys, and anyway the thing couldn’t even get off the ground due to the intervention of a humble Franciscan friar who came to say, so the lady was dressed in a way that was a bit too revealing, fine; so instead of praying she was constantly working her chewing gum, fine; but the transistor radio, crackling with the silly songs of that profane festival, had better be turned off.

“If that’s the way it is, we’ll go outside,” replied Palmira, full of decorum, and she put the accent on “we” so the little friar would understand that she would also be depriving the cult of Saint Francis of her husband who, if he had married her without so much as discussing it, must be the kind of jerk who did everything other people wanted him to do.

But her husband, without taking his eyes off of the sacred painting, replied, “You go outside, and don’t break my balls.”

Signora Palmira looked at him, at first incredulous but then very quickly indignant, hating him more than she had hated him up to that moment, because she could see perfectly well that the jerk would not be moved. So she stiffened her back and, still working her gum and listening to the radio, went out to the square in front of the church where, little by little, her anger waning but her self-pity waxing, she began to think that their marriage, which she had firmly desired not to say plotted for, might actually be a calamity if the man she married, instead of taking her to the San Remo Festival, had brought her to this place for losers that made her feel so sad.

Eight days they stayed in Assisi, and she never again set foot in the Basilica, where that friar had treated her so discourteously. She stayed in bed with her trusty radio and her thoughts, or, still listening to the radio but with fewer bad thoughts, she would go sit in the sun at a table in some outdoor café.

He, on the other hand, outfitted with a hunting stool he had bought for himself, spent the whole day, until the light grew too dim, sitting in front of his fresco, apparently a dullard but actually searching, although confusedly and at bottom without a lot of torment, a more uplifting justification for having found himself in the world talking to birds. Who knows, maybe he would have managed to find that more uplifting justification, or rather, in plain words, he might at least have gotten closer to his own state of holiness, but for the fact that in him, as in any other being, but in a form certainly more exalted and distinct, there was both good and evil, the wolf and the little boy, so that, after all that daytime uplift, when darkness fell, in a sort of schizophrenic dichotomy, he was overcome with lust and wantonness. So, in the double-room with bath at the pension “Sister Moon,” he threw himself like a mad man on the body of his bride.

He relished that body to the point of delirium, not only its perfectly modeled buttocks, but also everything about it that was soft and curvaceous. And there was plenty to relish. Abundant, firm breasts, round tummy, raised pubic mound, glorious hips, shoulders and arms and feet. He gazed at it, caressed it, kissed it, licked it, all the while emitting sounds of sensual gratification.

The bride, gum in her mouth and radio at her ear, let him do as he wished. Only sometimes, when it seemed to her that he was dragging things out a little too much, she would intervene to ask, “But when are we going back home? We can’t spend all this time away from the factory!”

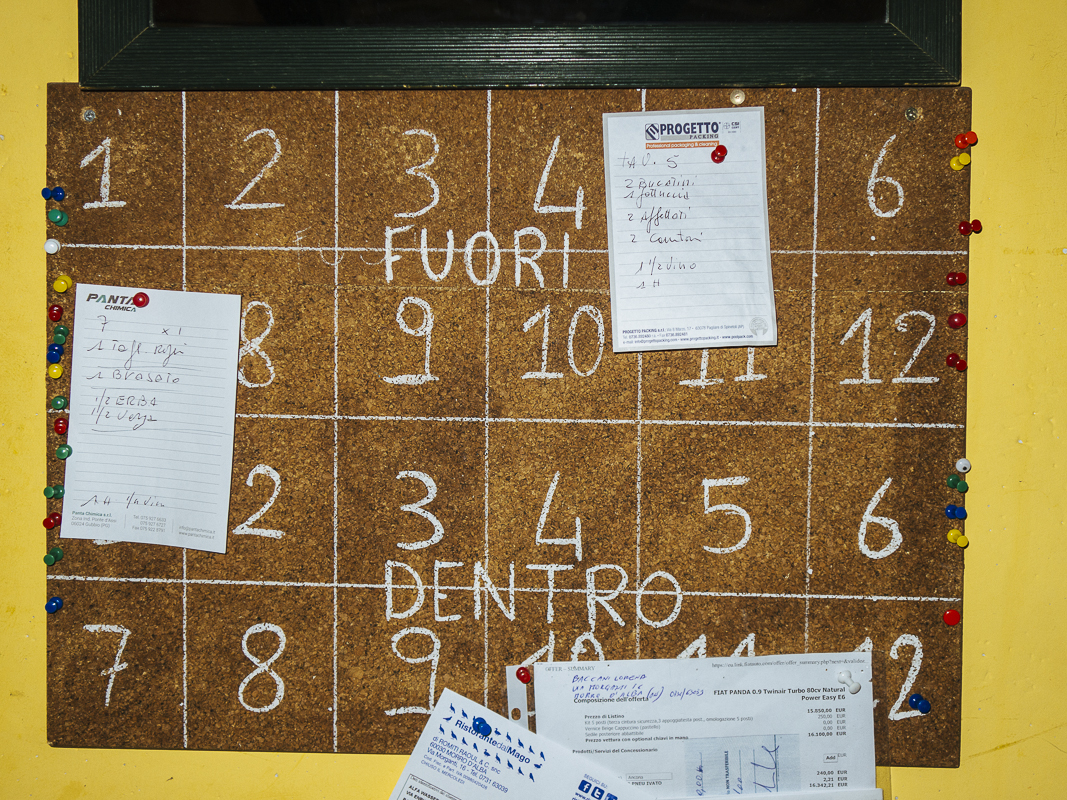

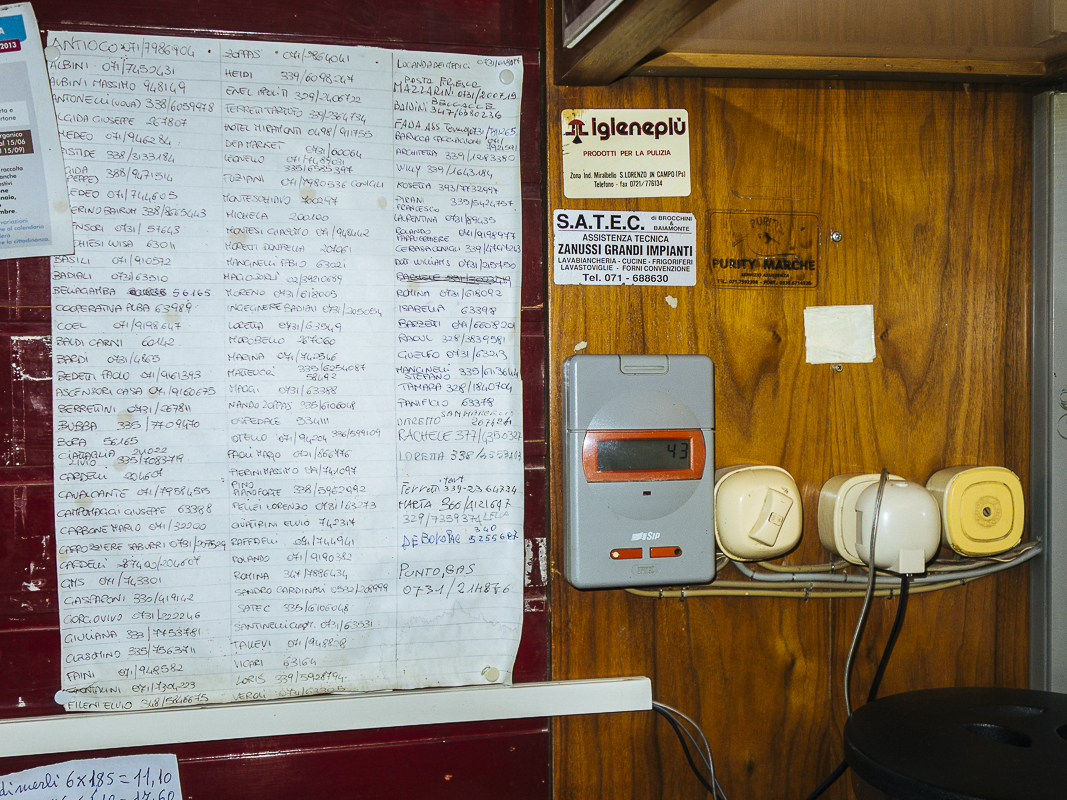

“Signorina Rosa will look after the factory,” he answered, still grazing.

And she took offense. “She’s deaf, blind, old, and brainless. What do you mean she’ll look after the factory.”

“She’ll look after it. She knows how things were done in my grandfather’s time, bless his soul.”

Signora Palmira would have liked to tell him exactly what she thought about his blessed grandfather and his entire family of nut cases, but she held back, waiting for a more opportune time. She felt, how to put it, as though she were expanding.

Anyway, the time eventually came for them to head home.

As soon as they arrived, Augustus the Second went to the door of the bedroom where his mother had shut herself in, and said, “I’m back, Mama. Everything went fine.”

He got, obviously, no response.

Signora Belinda, as everyone knew by now, was not doing well at all. Her personal physician, Doctor Bardi, had come to examine her a few days ago and he was worried. Unable to come up with a diagnosis, he had advised hospitalization, but the patient had said no, and had refused to allow the doctor to examine her again. So her personal physician was kept outside the door too, asking her questions that never got an answer: Had she had a bowel movement? Did she have a fever? Feel pain, nausea, dizziness? Nothing.

A few days later, however, she sent for her son. She didn’t even look at him. She waited for him to come to the side of the bed, and said to him, “You’re the one who wanted me to die.”

Augustus the Second did not comment.

After a long pause, Signora Belinda added, “Your father was a halfwit, you’re a total nitwit, and your wife is a whore.”

Even then Augustus the Second made no comment.

Signora Belinda let an even longer silence go by, summoned her energies, and concluded, “The child that will be born is not yours. The father is Carlo Vigeva. And now, get out of here, let me die in peace.”

She died during the night, without any further disturbance.