The issue of male prostitution has already come up on several occasions, and we really cannot avoid this lamentable practice if we wish to produce a more or less comprehensive account of the diverse forms in which uranian life manifests itself in Berlin.

Like any other metropolis, Berlin has both female and male prostitution. The two are closely related in their origins, nature, causes and consequences. Here, as elsewhere, there are two reasons that always come together, of which one or the other soon prevails: inner inclination and outward circumstances. Those who fall prey to prostitution are marked from youth onwards by certain peculiarities of which the most pronounced is an urge for fine living combined with a tendency to laziness. If the external circumstances are favourable to these qualities, that is, if the parents are well-off, the young person will be safe from prostitution. But if there is domestic squalor, a miserable livelihood, unemployment, lack of accommodation and possibly the greatest of all problems, hunger, then stable, steadfast characters might well withstand, but the weaker will seek out the ever-present temptation, succumb to it and sell themselves, ignoring their mothers’ tears.

There are humanitarians who expect improvement to come from freedom of the will and others from force of circumstances; one longs for education and religion, the other looks to the state of the future. Both are overly optimistic. Those who wish to help must strive to improve conditions from within and without, such that girls and youths are not obliged to sell themselves, and help improve people with particular consideration for the laws of inheritance, so that the obligation to sell oneself as a product falls away.

You might say that is impossible, but I say he who surrenders is lost.

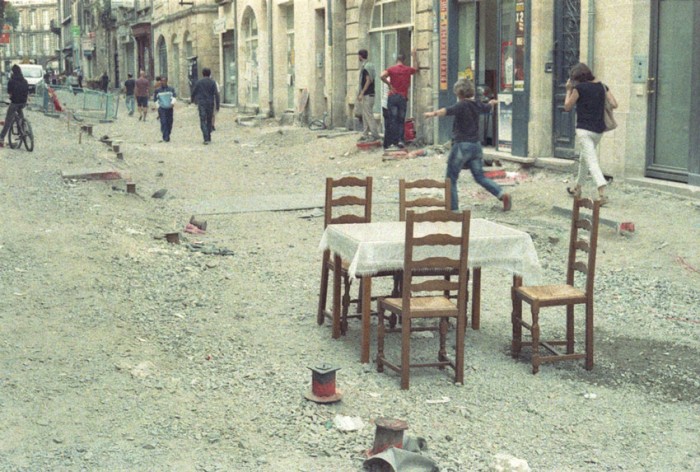

Prostitution’s sphere of activity is the street, particular areas and squares, the so-called ‘beats’. A homosexual showed me a map of Berlin on which he had marked the ‘beats’ in blue; the number of places thus designated was not inconsiderable.

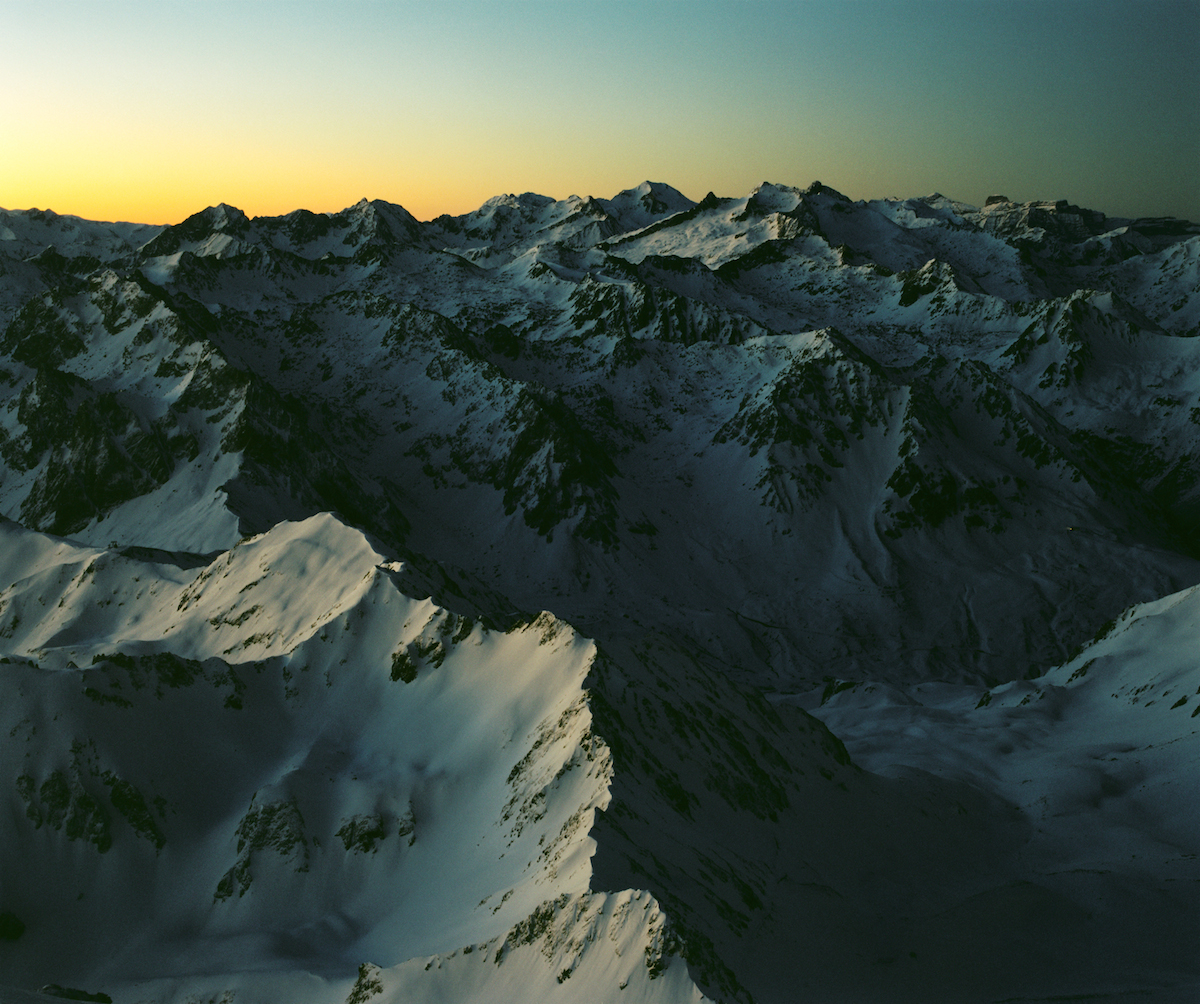

Since time immemorial the various parts of the Tiergarten have played their own particular part. There is no other forest that is so interwoven with human destiny as this park measuring over 1000 acres.

It is not the beauty of its landscape nor its artistic ornaments that lend it significance, but people – their lives, loves and laments. From early morning, when the well-to-do work off their meals on horseback, until midday, when the Kaiser undertakes his ride; from early afternoon, when thousands of children play in the park, until late afternoon, when the bourgeoisie goes strolling, each pathway has its own character, in every season, in every hour. If Emile Zola had lived in Berlin I do not doubt that he would have investigated these woods and that his enquiries would have resulted in another Germinal.

But when evening falls and the sun turns to other worlds, the breath of dusk mingles with the questing, yearning breath from millions of earthly beings, all part of that global spirit that some call the spirit of fornication but which in truth is just a fragment of the great, powerful drive, higher than everything, lower than anything, which ceaselessly shapes, prevails, forges and forms.

Couples meet at every crossroads in the Tiergarten – see how they hasten to one another, how joyfully they greet each other and stride into the future pressed close in conversation, see how they alight at the now empty benches and silently embrace, and how the high, inalienable kind of love sits side-by-side with the more vendible variety.

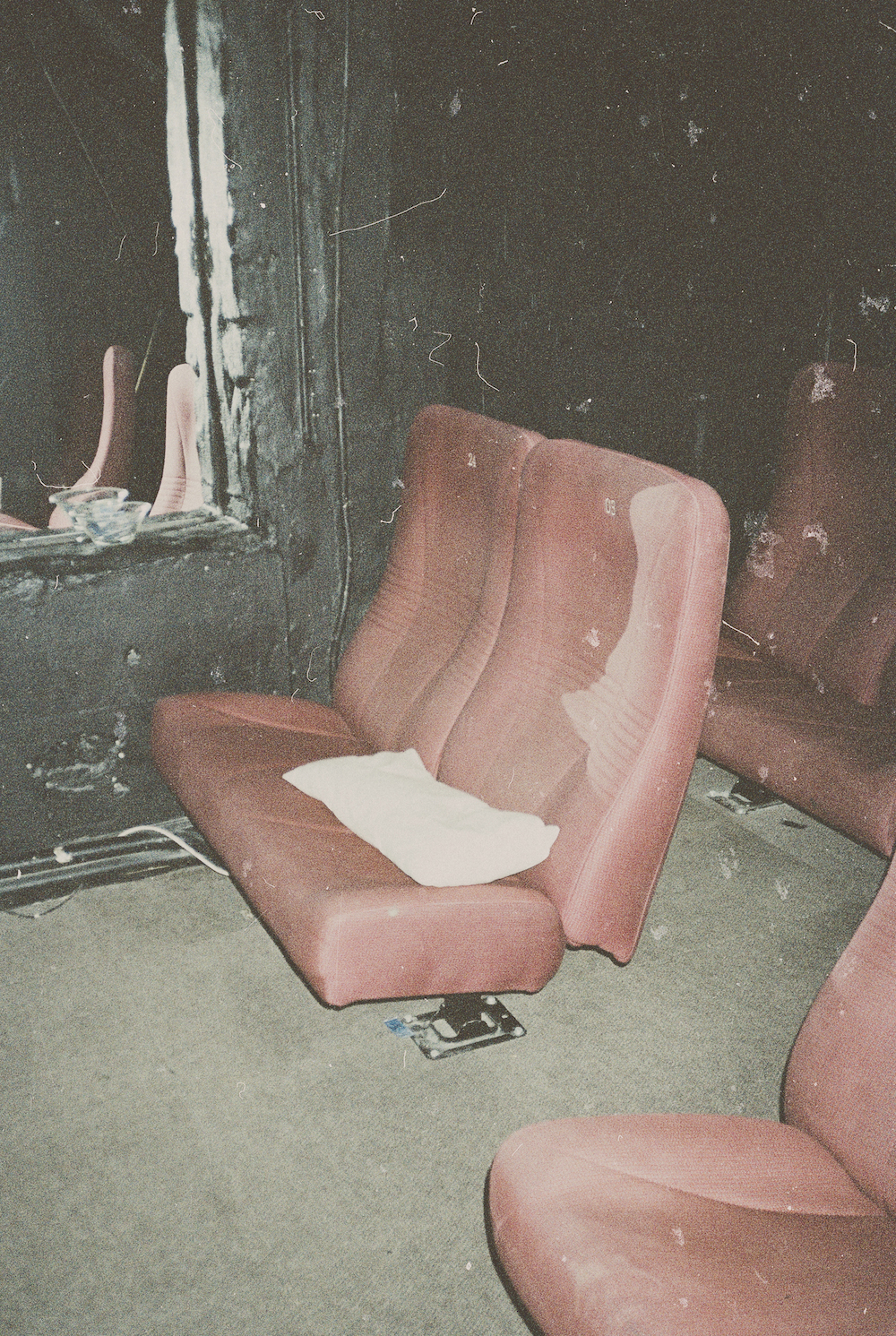

Women offer themselves for sale on three widely distributed paths, the men on two. While female and male prostitution are intertwined, here each has its own ‘beat’. Of the men’s, one is filled every evening almost exclusively by cavalrymen, their sabres glinting queerly in the dark, while the other, quite a long stretch, is largely occupied by those reckless lads apt to refer to themselves in Berlin dialect as ‘nice and naughty’. Here you will find one of the typical half-moon-shaped Tiergarten benches, where from midnight onwards thirty prostitutes and homeless lads sit close to each other, some fast asleep, others yelling and shrieking. They call this bench the ‘art exhibition’. Now and then a man comes along, strikes a match and illuminates the row.

Not infrequently the lads’ shrieking is interrupted by a shrill cry, a call for help from one robbed or manhandled in the thicket, or the snatches of music wafting over from the Zelten are punctuated by a sharp bang, reporting of one who has answered the question of life in the negative.

And anyone looking for the colourful city characters erroneously reported to be extinct will find no shortage of them in the Tiergarten. See the old lady there by the waters of Neuer See with the four dogs? For forty years, with brief intermissions during the summer, she has been taking the same walk at the same time, always alone, ever since her husband died of a haemorrhage on her wedding day in transit from the registry office to the church. That desiccated, hunched apparition with the shaggy grey beard? He is a Russian baron who seeks out a solitary bench, sits down and cries ‘rab, rab, rab’, a sound much like the crowing of a raven. This mating call draws the odd ‘cheeky grafter’ from obscure paths – his friends, to whom he distributes the ‘dough’ left over from his daily earnings, usually three to five marks.

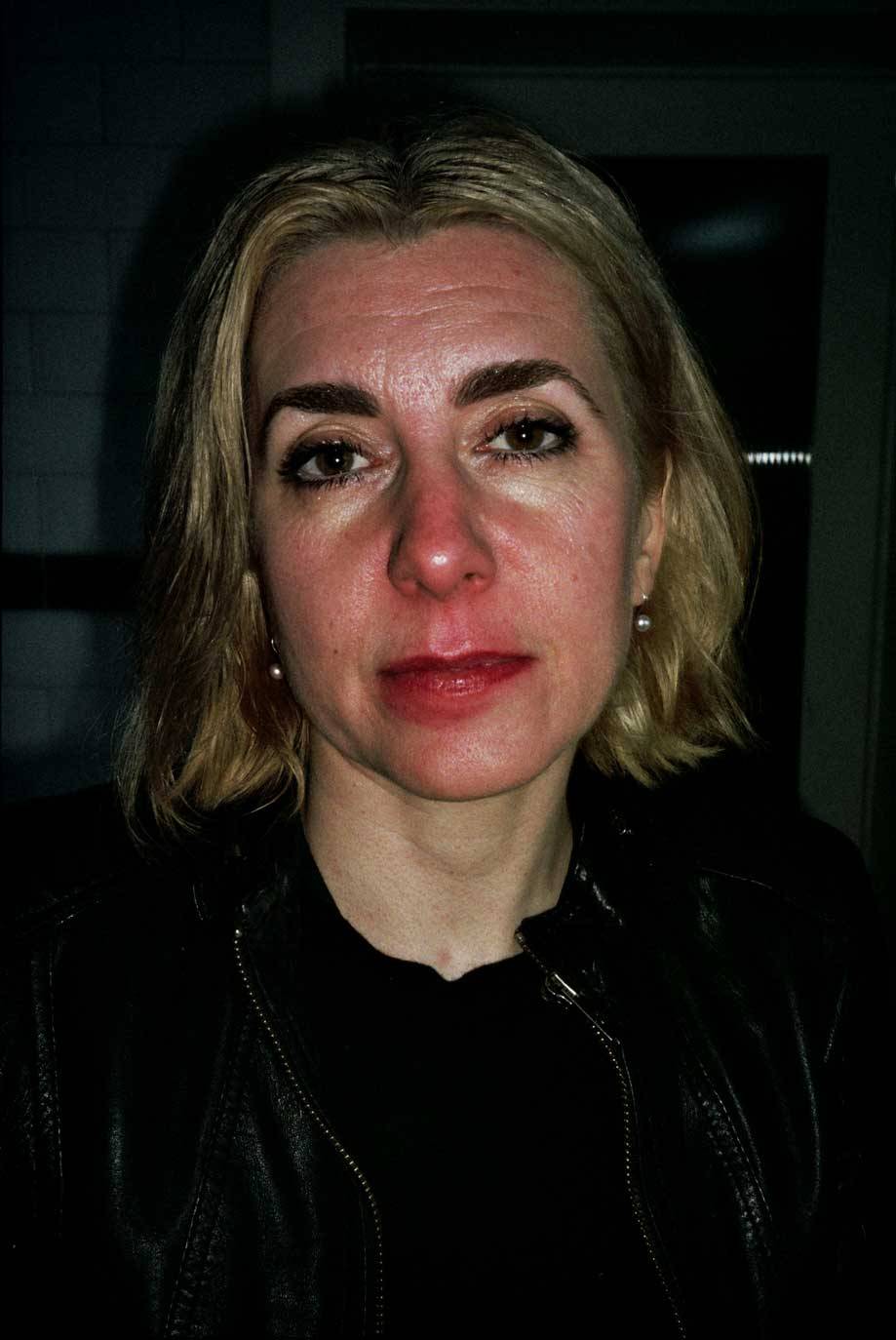

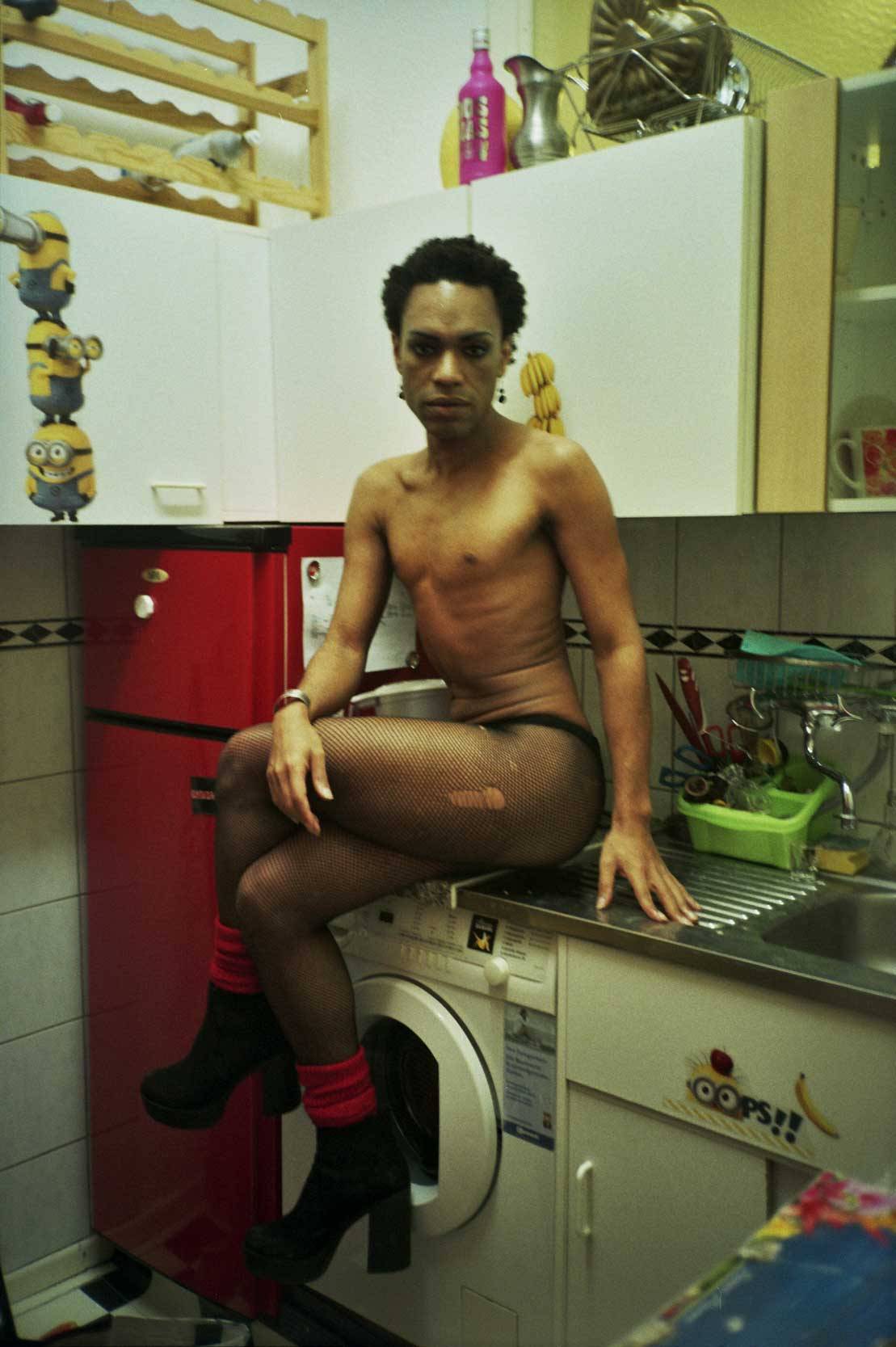

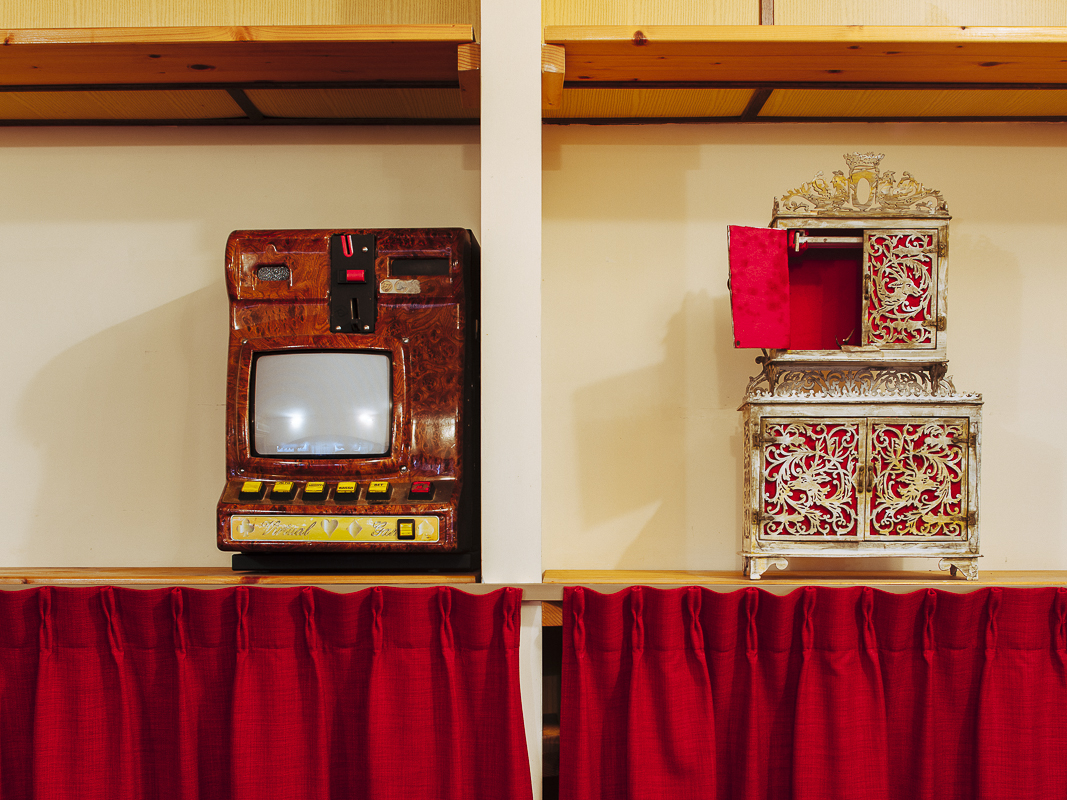

Male prostitutes can be divided into two groups – those who are normally sexed and those who are themselves homosexual, or ‘genuine’. The latter are often particularly feminine, and some occasionally wear women’s clothes, a practice met with particular disfavour by female prostitutes. This is ordinarily the only casus belli between the two groups, because experience has shown that neither would rob the other of clientele were it not for this fraudulent representation. I once asked a fairly well educated prostitute to explain the good relations between female and male prostitutes. ‘We know that every john wants what he wants,’ she answered.

There are often unusual pairings among Berlin prostitutes. Normal male prostitutes, the so-called dollboys, not infrequently conduct cooperative ‘work’ with normal female prostitutes. I have even heard tell of pairs of siblings of whom both sister and brother fall prey to this lowly work; often two female and not infrequently two male prostitutes will cohabit, and finally there are also cases of female homosexual prostitutes who take male homosexual prostitutes as pimps, finding them to be less brutal than their heterosexual colleagues.

It is established fact that there is a large number of homosexuals among female prostitutes, estimated at 20 per cent. Some might wonder at this apparent contradiction, after all commercial prostitution primarily serves the sexual satisfaction of the male. Often it is said that they suffer from surfeit, but that is not actually the case, because it has been proven that these girls usually know themselves to be homosexual before taking up prostitution, and the fact of their homosexuality only serves to prove that selling their bodies is simply seen as a business, one they regard with cool calculation.

The relationships between prostitutes are noteworthy. Even here the system of double morality has made its presence felt. Because while the manly, active partner, the ‘father’, is at liberty, free to pursue female contact beyond the shared bedchamber, he demands the utmost fidelity from the ‘female’, passive partner when it comes to homosexual activity. When this fidelity is breached he exposes himself to the most grievous abuse. It also comes to pass that the manly partner forbids the womanly partner from pursuing work for the duration of their affair.

The female street prostitutes of Berlin also maintain diverse relations with uranian women of the better social circles, and on the street they might even make advances to women who seem homosexual. Here it is worth noting that the fees for women are much lower, and might indeed be waived altogether in some instances. One young lady who certainly appears decidedly homosexual reported to me that prostitutes had made her offers of 20 marks and more on the street. The poor example of both female and male prostitution is not just a threat to public morality, and to public health – for it is far from uncommon that infectious diseases from scabies to syphilis are passed through male prostitution – but also public safety to a large degree.

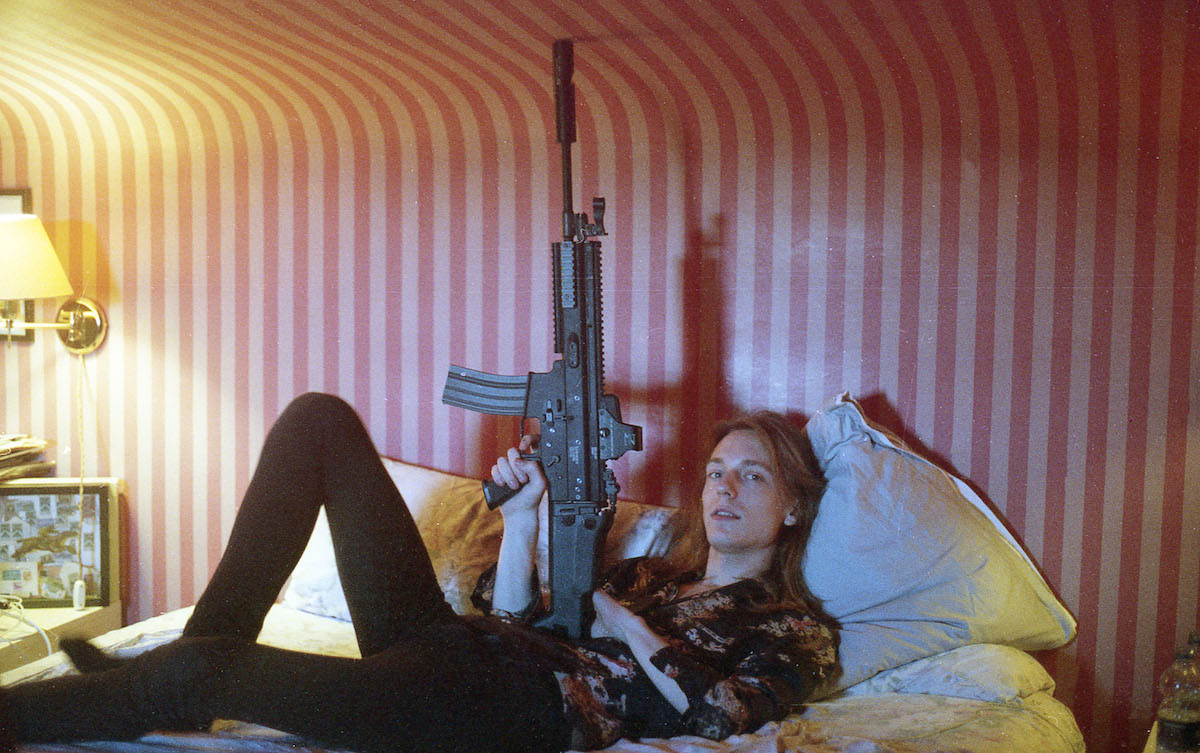

Prostitution and criminality go hand in hand; theft and burglary, blackmail and coercion, forgery and embezzlement, every sort of violence; in short, every possible crime against person or property are a way of life for most male prostitutes, and what is particularly hazardous is that in most cases the anxious homosexual fails to report such crimes.

While twenty of Berlin’s uranian population of 50,000 souls – this figure is surely not too high – are caught on average by the ‘long arm of the law’ every year, at least a hundred times more, that is, 2000 a year, fall victim to blackmailers who, as the Berlin Criminal Police will gladly attest, have built a widespread and particularly profitable profession from the exploitation of the homosexual nature.

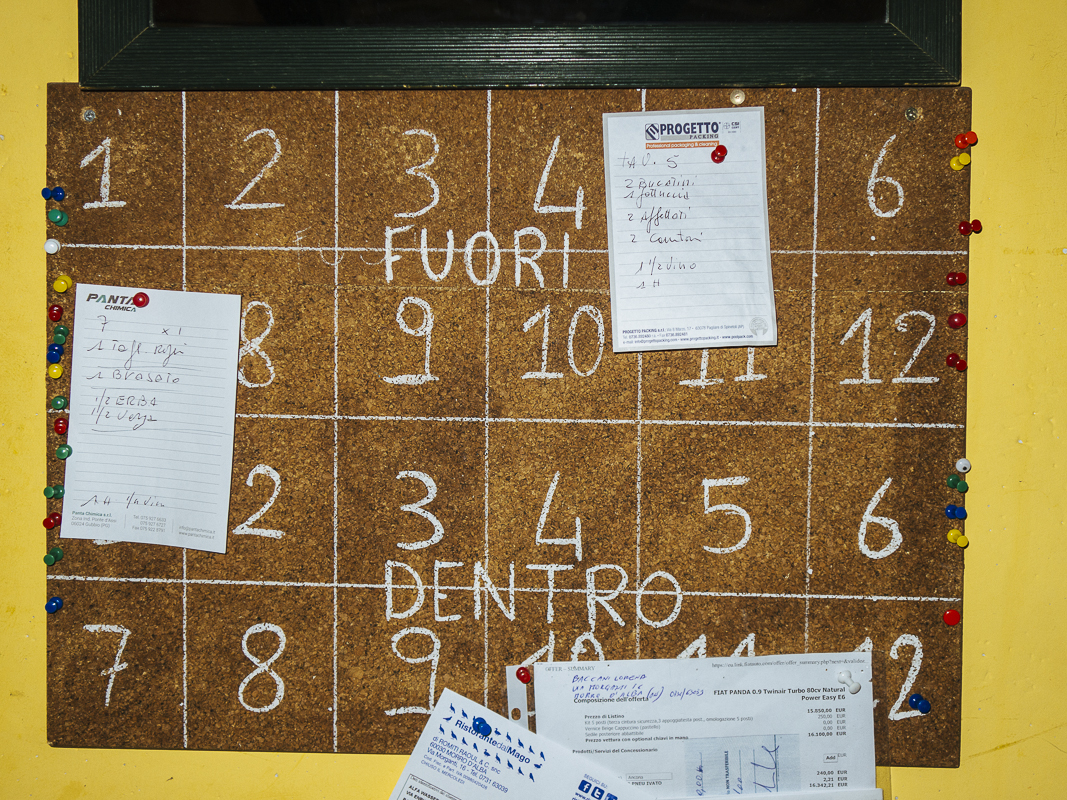

The close links between prostitutes and criminals also arise from their use of the same shared criminal jargon. If the ‘beat boys’ are looking for their quarry, they call it ‘going on a collection tour’, blackmail itself they designate in various degrees: ‘scalding’, ‘burning’, ‘busting’, ‘fleecing’, ‘clipping’, ‘dusting down’, ‘plucking’ and ‘clamping’. Here it is worth noting that in Berlin there are also criminals who specialise in ‘plucking’ male prostitutes by threatening them with a charge of pederasty or blackmail. They categorise the ‘schwul groups’ according to liquidity into ‘mutts’, ‘stumps’ and ‘gentlemen’, and the looted money they refer to as ‘ashes’, ‘wire’, ‘dimes’, ‘gravel’, ‘rags’, ‘dosh’, ‘meschinne’, ‘monnaie’, ‘moss’, ‘quid’, ‘plates’, ‘powder’, ‘loot’, ‘dough’, ‘cinnamon’, and for gold coins, ‘silent monarchs’. To have money means ‘to be in shape’, to have none is ‘to be dead’, should something get in their way they say that ‘the tour has been messed up’, ‘bunking’ means running away, ‘snuffing it’ is dying, and if they are picked up by the ‘claws’ – the criminal police, ‘the blues’, or policemen – they call it ‘going up’, ‘flying up’, ‘running out’, ‘crashing’ or ‘going flat’. That is when they are brought to the ‘cops’, or the police station, then to the ‘nick’, the remand prison, and finally, as the euphemism goes, they move to the ‘Berlin suburbs’, understood as Tegel, Plötzensee and Rummelsburg, the locations of prisons and work houses. Only rarely do they leave better than they arrived. Well-to-do uranians often try their hardest to save prostitutes from the street, but only in very few cases do they succeed. Many ‘feast on memories’ when they get older by ‘drilling’ small sums of money out of known homosexuals with whom they once crossed paths, which they refer to as ‘collecting interest’ or ‘tapping’.